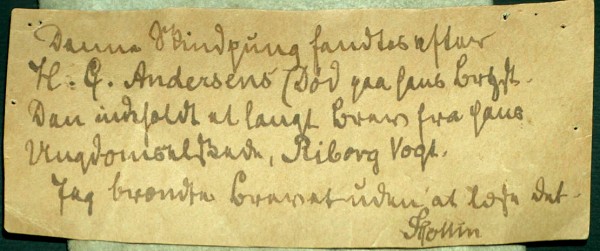

Andersen’s pouch and the note about it by Jonas Collin Ir.: “This leather pouch was found on the chest of Hans Christian Andersen after his death. I t contained a long letter from the love of his youth, Riborg Voigt. I burned the letter without reading it. J. Collin”.

The relationship grew into a close and enduring friendship. In The Fairy Tale of My Life he tells of a little event at Christmas 1845, when both were in Berlin. He complains about not having heard from her; he had been so sure of being with her that he had refused every other invitation (though he writes that he is only telling her this). This is greatly exaggerated, but she takes it literally, pats him on the cheek, and says “Child!” Whereafter she decorates a Christmas tree for the New Year, where all the presents are for him, but where there is also a lady friend present, to avoid any misunderstanding. I do not think one needs to have any other details about Andersen and Jenny Lind in order to appreciate how beautifully she knew how to transform undesired passions into a sisterly-motherly poetry, which he drank from in full draughts.

Andersen so arranged it that a leather pouch was found round his neck when he died, a pouch containing a letter from Riborg. The letter was to be burnt unread. He could not possibly have worn this all his life: as the matter-of-fact Professor Brix observed, it would have fallen to pieces. So it was arranged. And what then? Attitudinizing can in some cases be the last resort in getting things said, also (or especially) in the case of great artists.

Attitudinizing can be most genuine; can, as art, be the point where a person lives full out, more genuine and more wide-ranging than in reality.

In Andersen’s heart there was more than the ugly duckling that became a swan, or the happy witless Clodpoll. His life was a fine fairy tale: not an almanac story about how all turns out as it should and the best man wins. In his heart there were also the Little Mermaid, who was drawn to an element in which she had to die; the Mother, who was good for something, though she ended up in drink; the Snowman that with unerring tragedy fell in love with a stove; and, apropos wooing, the Prince who had to humble himself, disguising himself as a swineherd and pop artist, in order to have any chance at all with the stupid princess. “You wouldn’t have an honest prince. ..but the swineherd you kiss for a musical-box! ”

That was Andersen’s judgement on the world when he was in a baleful mood. But it is seldom that his knowledge of the wasted, the rejected, the failed devolves into severity. You would not have the best, nor the next-best in me: or what everyone else can imitate!

The old bachelor found his quiet home in the end, in his own good company. He is said to have remarked as an old man: “Now I only go out once a week, so they can please themselves!”

But he did want to be found wearing that leather pouch. Perhaps because it testified to his inmost pride: fidelity to all that was lost. Like the clergyman’s painting that wanted to include the reality of death on equal terms with that of life. A testimony to everything that never came to anything -though it was good for something.

The author: Lise Sørensen, born Copenhagen 1926. Married to author Erik Knudsen. Has published five collections of poems, a volume of short stories, a children’s book and two collections of essays which include articles on Hans Christian Andersen. She is professionally employed as a publisher’s reader.