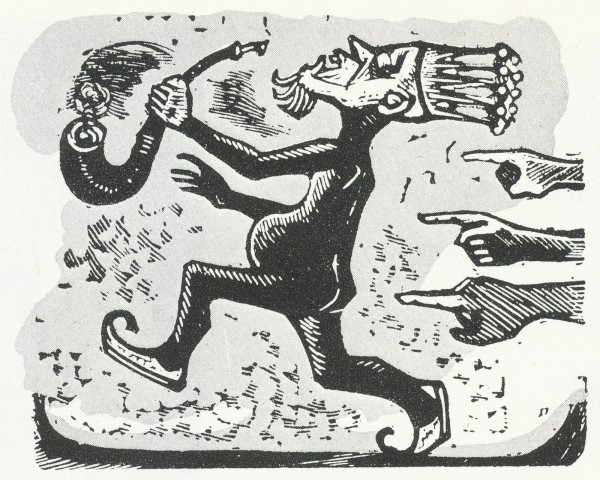

Huang Yung-Yu. Illustration of Yeh Sheng-tao’s The Scarecrow. Peking 1961.

Common decency

Regardless of choice of milieu and basic approach, the many artists have to take sides in a third respect, both as regards weaving and as regards common decency. What are the weavers to be doing? What is the meaning of the words ‘new clothes’? The subject is not particularly interesting, but a position has to be taken. Vilhelm Pedersen, who even provides the Little Mermaid’s underwater statue of the prince with an apron, of course draws the emperor in his shirt, and this reasonable expedient is followed by many, while the aforesaid Rumanian and others give him a loin-cloth or long trousers. Few seem to have missed the complete physical exposure, although a young woman ‘ideology-critical’ writer has recently confessed to doing so in Pedersen’s interpretation.

In fact there have been artists, quite early, who have shown the emperor with nothing on but insignia, sashes or the like, but they always, to be sure, mitigated the sight by having the weavers or the crowd ‘stand in the way’. The Finn Erkki Tanttu (1955) and the internationally known Pole J anusz Grabianski a few years later gave the emperor almost identical costume and bulk, in front of the mirror and in the procession.

To this degree of decency belongs Bertall’s drawing for the classic French edition of 1856. But here we return sharply from the spirit of decorum to the very robust sphere of politics: the title in all editions is’ Les habits neuts du grandduc’. All right, there are so many retouchings in the Andersen translations. But the list of contents of the first impression gives, not ‘grand duke’, but ’emperor’, as usual. A translator, publisher, censor -who knows? -had scruples; but an editor or printer has omitted, unintentionally or deliberately, to alter Napoleon Ill’s title in the contents table!

…We will leave our subject and allow His Majesty to gallop naked off to the left, pursued by an incensed populace that had already lost hundreds of heads and refused to submit to the stripped emperor’s unbending tyranny. First he would not listen to criticism; then he would only wear the new clothes; then, under pain of death, he would have forbidden any sort of noise within hearing of his processions. How fair and right that high and low set upon and dethroned this stupid and wicked ruler .

This further development is by Yeh Sheng-tao and the artist Huang Yung-yu, and is from the English-language book The Scarecrow, Peking 1961. ‘Such works are mirrors. ..’ as Lichtenberg’s aphorism begins.

Literature: Les habits neufs de l’empereur en vingt-cinq langues, pub lie par Louis Hjelmslev & Axel Sandal. Copenhague 1944. Erik Dal: Udenlandske H. C. Andersen-illustrationer (Foreign H. C. Andersen Illustrations. 100 pictures from 1838 to 1968). Copenhagen 1969.

The author: Erik Dal, born 1922, dr phil 1960, was formerly with the Royal Library and the Danish School of Librarianship and is now Administrator of the Danish Language and Literature Society. His extensive scholarly work has chiefly concentrated on folk-ballad research, Danish literature of the seventeenth century, Hans Christian Andersen and bibliography.